We collect basic website visitor information on this website and store it in cookies. We also utilize Google Analytics to track page view information to assist us in improving our website.

By: Summer Graham

The topic of shifting native plant ranges touches on many of the themes that have been (or will be) covered on the Network of Nature blog page. What classifies a plant as “native”? How is the climate changing, and what does this change mean for ecology? What is the connection between native wildlife and native plant species? Each of these topics can be difficult to dissect on their own. Mix them together, and the picture becomes even more blurred.

Let’s start with what we know. As the climate changes and global temperature warms, it might be expected that species will move “up” (north and/or to higher elevations) to remain in environments that suit their traits. A study in California found just that, but they also found some more concerning evidence. While both plants and animals were found to be shifting their ranges, wildlife was doing so at a much faster rate (Wolf et al. 2016).

Over the past century, only 12% of native plant species are moving ranges upwards at a significant rate (Wolf et al. 2016). Even more alarming, a greater proportion of non-native and invasive species (27%) were on the move, causing concern that as native species move upwards, they will find would-be suitable habitats already colonized by non-native species (Wolf et al. 2016). This combination of factors means that the faster moving wildlife will find themselves in potentially unsuitable, non-native habitat, and this breakdown of ecological relationships could have unknown consequences for species survival.

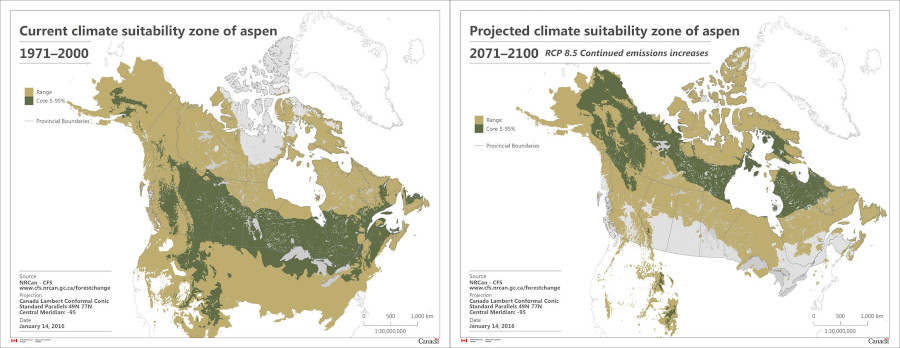

Current (1971–2000) versus projected (2071–2100) climate suitability zone of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides). Image courtesy of Natural Resources Canada.

The results of a warming climate may not be consistent across the globe, however. Bezeng et al. (2017) found that in parts of South Africa, climate change may actually result in a reduction of area suitable for current invasive species that are present on the landscape. However, there were some species that showed potential to expand ranges due to changes, and there is also the opportunity for new invaders to appear when shifts occur (Bezeng et al. 2017).

So, where do we go from here? If we accept that species (especially native ones) might not be able to move and adapt fast enough to survive the current shift in appropriate habitat, what (if anything) can we do?

Assisted migration is the human-assisted movement of species (plants or animals) to more suitable habitats, and it is a widely debated topic in terms of risk, viability, resources, and ethics. In Canada, many provinces and territories already have seed transfer guidelines for planting of seed from certain regions to ensure genetics are suitable for an area (NRC 2016). B.C. and Alberta are two examples of jurisdictions that have modified these guidelines by extending seed transfer zones 200 metres higher in elevation, effectively taking a small step towards assisted migration (NRC 2016).

Assisted migration can be done on multiple scales, each with their own level of risk. The lowest risk option is assisted population migration, where species are only moved within their historic or known range. Then there is assisted range expansion, where species are established just outside their established range, but to areas that would feasibly be expanded to through natural dispersal methods such as wind, water, or dispersal by animals. The highest risk is associated with assisted long-distance migration, where species are moved to areas far outside a “natural” dispersal area.

Regardless of the scale on which it is implemented, assisted migration should be backed by research on species genetics, viability in an introduced area, natural dispersal, and the risk posed by introducing or moving certain species. Although this process may be slow, it is likely still faster than allowing species to move at a natural pace, and we may reduce the risk of important native species being left behind.

Climate Central. “Climate Change is Leaving Native Plants Behind.”

National Geographic. “Half of All Species are on the Move – And We’re Feeling It.”

Yale Environment 360. “As World Warms, How Do We Decide When a Plant is Native? “

Join our email list to receive occasional updates about Network of Nature and ensure you get the news that matters most, right in your inbox.