We collect basic website visitor information on this website and store it in cookies. We also utilize Google Analytics to track page view information to assist us in improving our website.

Written by Summer Graham

When we see a field of flowers, the thought of pollinators is often not far behind. Why can’t the same be said when we look at a field of vegetables, or our dinner plates?

The fact is that pollinators (like bees, moths, butterflies, and birds) are responsible for about 1 in every 3 bites of food we eat every day! Without pollinators, we would be unable to produce crops at the rate we currently do, and the resulting food insecurity would be devastating.

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from the male anther of a flower to the female stigma of another flower. This transfer is required to produce seeds, which develop when pollen goes to another flower of the same species.

Seeds are one method that plants use to reproduce and pass on their genetic diversity.

Cross-pollinating species require a separate individual of the same species nearby and a vector, such as wind or a pollinator, to transfer pollen. Pollination doesn’t always require pollinators; in fact, some plant species are self-pollinating, meaning their flowers can fertilize themselves.

Maintaining pollinator diversity is just as important as supporting and protecting pollinators. If we rely on only a handful of species to pollinate all our crops, we risk large-scale food shortages if a disease or other disaster was to impact certain pollinator populations.

Some pollinator species are specialists (pollinating only one or two specific types of plants) instead of generalists (able to pollinate many species). For example, bees and flies visit and pollinate over 90% of the world’s major plant types, while other species, like birds, bats, butterflies, moths, ants, and beetles visit fewer than 6%.

Other species that might pollinate specific plants include cockroaches, mice, squirrels, monkeys, lizards, and even snails! Just because these species are not significant pollinators within our agricultural system, does not make them any less important to protect. The species pollinated by these specialists may rely almost solely on them to be able to reproduce, and so protecting pollinator diversity maintains diversity on other levels in our ecosystem as well.

squirrels, monkeys, lizards, and even snails! Just because these species are not significant pollinators within our agricultural system, does not make them any less important to protect. The species pollinated by these specialists may rely almost solely on them to be able to reproduce, and so protecting pollinator diversity maintains diversity on other levels in our ecosystem as well.

Some key threats to pollinator populations include habitat loss and disturbance, habitat fragmentation, pesticide poisoning, and competition with exotic/introduced pollinator species. Here are some easy things you can do at home to help support your local pollinators!

Protecting pollinators is about more than just saving the bees. We need to shift to more sustainable and efficient methods of food production that help all species of pollinators, not ones that harm them. By promoting native biodiversity on the landscape, we can enhance habitat for more pollinator species, and ensure that sustainable food production is available for generations to come.

Pollinator.org – Bigger than Bees

Diversity, Importance, and Decline of Pollinating Insects in Present Era

Wikipedia – List of Crops Pollinated by Bees

Written by: Summer Graham

Plants and animals within an ecosystem interact with each other through a variety of mechanisms. Some plants and animal species become so dependent on one another that they can co-evolve , meaning that one species can affect another species’ evolutionary adaptations because of the reproductive success gained by interacting with one another. These natural interactions between species gained over thousands of generations can be interrupted by replacing native flora with non-native flora, and can negatively impact the wildlife that rely on these relationships for success. Here we will examine different types of interactions between plants and animals and discuss some of the evolutionary traits that have become apparent as a result.

Herbivory

One of the most common interactions between plants and animals is  herbivory. The pressures of herbivores consuming plants over thousands of generations may result in plants evolving compounds that deter wildlife (such as toxins in leaves or spicy fruit). Although herbivory is often seen as beneficial to wildlife and detrimental to plants, partial grazing by herbivores can also benefit plant communities. For example, Tent Caterpillars grazing on leaves in canopy trees in a forest can lead to an increase of sunlight in the sub-canopy, shrub layer or forest floor, which can benefit the growth of these lower species.

herbivory. The pressures of herbivores consuming plants over thousands of generations may result in plants evolving compounds that deter wildlife (such as toxins in leaves or spicy fruit). Although herbivory is often seen as beneficial to wildlife and detrimental to plants, partial grazing by herbivores can also benefit plant communities. For example, Tent Caterpillars grazing on leaves in canopy trees in a forest can lead to an increase of sunlight in the sub-canopy, shrub layer or forest floor, which can benefit the growth of these lower species.

A classic example of a close relationship between herbivore and plant species are the Monarch Butterfly and Milkweed (Asclepias sp.). Monarch larvae only eat Milkweed species, so adult Monarchs will seek out these plants specifically to lay eggs on so that caterpillars will have easy access to their food source when they hatch. Because Milkweed provides larval Monarchs with their only food source, this interaction is critical to the success of Monarch reproduction. Unfortunately, adult Monarchs can mistake European Swallowwort (Vincetoxicum rossicum) as native Milkweed and mistakenly lay eggs on this invasive, non-native species resulting in larvae that are unlikely to survive.

Mimicry

Mimicry

Another interesting type of plant and wildlife interaction is mimicry. This occurs when wildlife evolves to mimic physical traits of plants that occur in their environments, allowing them to camouflage and hide from predators or easily hunt unsuspecting prey. In Canada, the Common Walkingstick (a.k.a stick bug) and many species of Katydids have evolved to resemble branches and leaves of the plants they live and feed on.

Pollination and Dispersal

Pollination and seed dispersal are similar interactions that allow wildlife to aid in the reproductive cycle of a plant species.

Pollination involves the transfer of pollen from one plant to another plant of the same species, allowing the plant species to successfully reproduce while providing the animal with a delicious snack. While some plants rely on wind for this to occur, others have evolved closely alongside native animal pollinators such as bees, butterflies, moths, birds, and bats. Many plants have evolved certain traits such as flower size, shape, smell, and colour to attract the specific animal needed to have successful pollination occur.

Seed dispersal occurs after successful pollination when the fruit and seed have developed in a plant. In order for seeds to successfully produce a new plant, they often need to be moved away from the parent plant. Similar to pollination, some plants rely on seed dispersal via wind, while others rely on wildlife to disperse seed in the following ways:

These are only a few different ways that plants and wildlife have evolved to interact together, and the relationships between them may be more complex than we currently know. From what we do know, it is clear that a shift from native to non-native vegetation can result in impacts to wildlife that have evolved to rely on critical interactions with native flora, making it all the more important to plant native species when we can!

Additional Reading

Brooklyn Botanic Garden - Plant/Animal Relationships

Plant Life - Animal Plant Interactions

Written by: Cole White

This year's UN World Wildlife Day celebrates forest-based livelihoods worldwide with the theme 'Forests and Livelihoods: Sustaining People and Planet'.

I grew up a family who hunted, fished, and worked in the woods. Later, like many young Canadians, I laboured as a piecework tree planter in the Boreal Forest. But even people I know who have lived their lives in Canada's most urban neighbourhoods feel a connection to woodlands—for example, my Torontonian friends who feel a sense of integration when they visit High Park, the ravines of the Don River, or the Rouge Valley.

Forests are a cornerstone of Canadian life. Everywhere, plants, microbes, birds, fish and a myriad of other creatures—including us—exist as part of a rich biological schema including forests. In Canada, forests sustain our culture, economy, spirituality, and livelihoods in ways that make this land and its people what they are.

Thirty-nine percent of Canada's land is forest, and this represents 9% of the world's total forests. The future is unwritten, but these numbers tell us that state of Canadian forests is a major variable in how climate change will play out worldwide.

Of course, it's a given that the changes we're already seeing—including severe wildfires, loss of ecological diversity, and the proliferation of invasive species that threaten tree populations—are expected to become more extreme in the coming years.

Adding to this, economic changes due to the pandemic, evolving consumer demands (for example, the decline of print newspapers and magazines), and international competition show that the preexisting commercial relationship between Canadian forests and people won't be the way of the future.

Increasingly, many Canadians are recognizing what forests give them, and asking what they can do in return. To me, this year's World Wildlife Day theme (and this inspired illustration for the event by Gabe Wong) expresses a hope that our global communities are affirming their relationships with forests and finding constructive ways forward that honour our interdepedence.

What's happening right now in Canada to support this? Our country's issues are diverse and so multifaceted, but these are a few trends I've noticed recently:

Indigenous forest management systems offer expertise informed by thousands of years' experience working with this land. The most recent Canadian census reported that 70% of Indigenous people in Canada live in or near forests. (I've also seen similar statistics for other parts of the world, and globally.) Increasingly, Indigenous people are reclaiming portions of their original territories and asserting their right to participate in self-governance, including forest management.

Indigenous involvement in sustainable natural resource management is helping to bring socio-economic benefits to communities and maintain cultural, recreational, and spiritual connections to the land. As reported beautifully in the National Observer, residents of B.C.'s Tŝilhqot'in Nation are using clean energy to develop a new land, water, and wildlife management area, supporting self-determination within their communities.

Coastal Guardian Watchmen also provide a model for what responsible land stewardship can look like in Haida Gwaii.

It's exciting to see collaborative efforts undertaken to synergize traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and settlers' science-based understanding of nature as complementary information systems.

In a recent lecture, Indigenous scholar and assistant professor Myrle Ballard at the University of Manitoba described how Indigenous expertise can inform scientific work.

The viewpoint has also been expressed poetically in the best-selling Braiding Sweetgrass, by botanist Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, who espouses radical gratitude to nature by asking that humans consider the question, 'What can I give in return for the gifts of the earth?'

Landscape architects and horticulturalists are inventing and adapting design models that enhance vitality for people and forests.

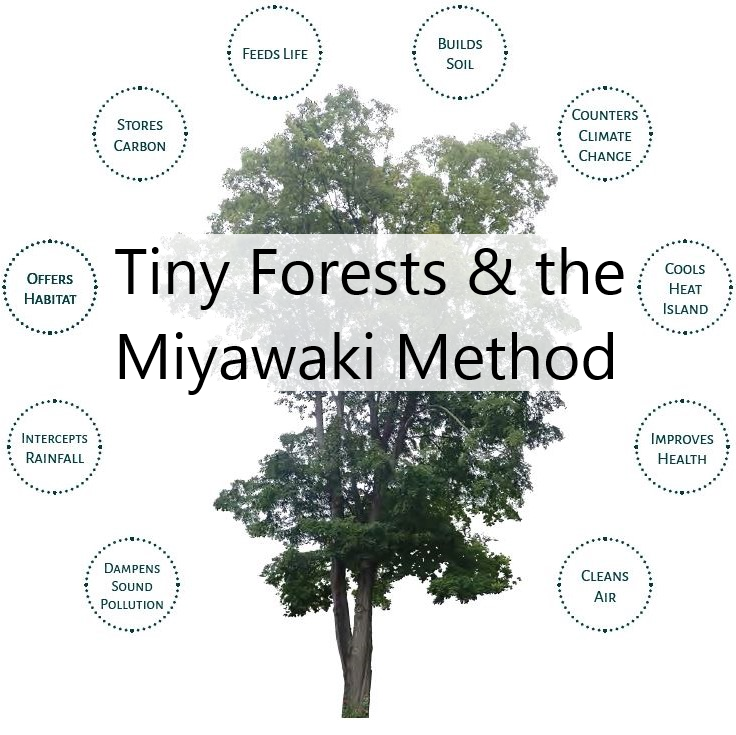

Planting individual trees is great, but what if you could fast-track the growth of a mini forest community in your neighbourhood? Network of Nature is piloting a new project on using the Miyawaki Forest technique to do just that in Canada.

Emerging technologies have their place in this work:

Remote sensing and artifical intelligence can give us new eyes in the sky to monitor our expansive Boreal Forest for extreme wildfires.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) analysis and interpretitive web cartography are being used to understand and educate Canadians about the value of our northern peatlands.

Ex-situ conservation methods carried out in sterile labs are providing hope for at-risk species, with researchers developing tissue culture and seed banking methodologies to preserve genetically unique local flora.

I think that Gen Z will grow up more attuned to ecological issues than any previous generation. One educational resource I noticed recently is this kid-friendly website, which includes a colouring book, advocating for the conservation of Wisqoq (Black Ash) populations in our eastern forests.

Black Ash(Fraxinus nigra) Black Ash is native to Eastern Canada and is used in traditional basket weaving. Populations are currently under threat due to the proliferation of Emerald Ash Borer.

|

|

This blog post is a snapshot of my personal reflections, and I'm sure I don't have all the pieces of the puzzle. Maybe you have something to add about how Canadians and forests can work together, or where this is all going. Do you know of something I should have mentioned here? Let us know!

For more information about World Wildlife Day events, which include a film festival, check out the offical website.

Join our email list to receive occasional updates about Network of Nature and ensure you get the news that matters most, right in your inbox.